WGSN meets Stellarium

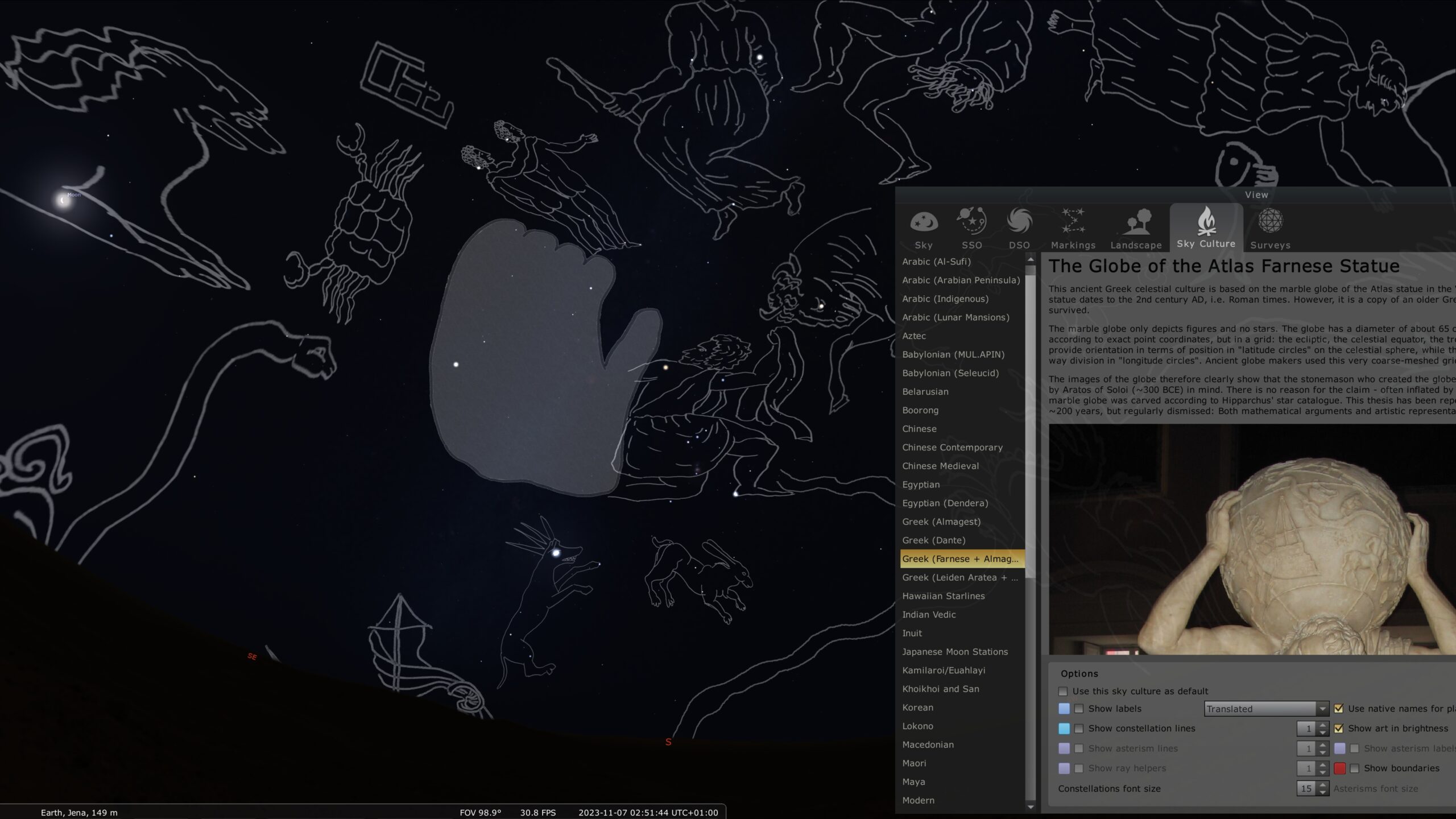

The Working Group Star Names (WGSN) and the Stellarium team met in Jena from 1 to 3 November 2023 to think about ways of managing cultural data together. Astronomy is a science that works across faculties: Astrophysics has admittedly been one of the pioneering sciences for large databases and other repositories since the 1970s and the beginning of the space or space telescope era. However, as soon as we go beyond astrophysics and include astronomy (i.e. all the other branches of astro-science), we leave the realm of established repositories and have to create new ones. The free and open-source software Stellarium allows contributions from researchers (whether ethnology, anthropology, history of science, cultural studies, philology…) and this has already been used many times. The repository currently has around 40 to 50 “sky cultures”, i.e. sets of representations of constellations, their names and descriptions. A “sky culture” consists of names for constellations, line figures and/or images of constellations, sometimes also names of individual stars, definitely a description (where does this culture come from, where is it located on Earth and how was the representation developed that is depicted in Stellarium) and a licence.

New Culture as an expression of respect

After the known star names (such as Vega) were officially written down in the first step (2016-2021), the question now is what strategies will be used to assign further star names. A question within the group are some fundamental strategic ones: Some of us think, we should limit the naming of stars to historical and indigenous names of stars and constellations and not use human names while others are more relaxed about this topic. We did decide that naming campaign suggestions from the public are only used to name stars fainter than 6.5 mag. For the bright stars, e.i. stars that are in principle visible to the naked eye, we should use traditional names. However, traditional star names are only given to stars 2 mag and brighter. Hence, for stars of 5 or 6 mag we could only use names of historical and indigenous constellations (that designate areas which include also these fainter “bright stars”). This would still give us enough names to label the roughly 8000 stars that are visible for the naked eye and we won’t need to invent eponymous star names: comets or lunar craters are named after people.

Die Sterne, die begehrt man nicht,

man freut sich ihrer Pracht

und mit Entzücken blickt man auf

in jeder heiteren Nacht.

[Joh. W. Goethe]

We don’t covet the stars,

one rejoices in their splendour

and we look up with delight

on every serene night.

[Joh. W. Goethe]

In addition, constellations have been invented in all cultures to symbolise general interpersonal values (of love, friendship, respect, sacrifice, recognition). Some of us think, such universal values and the legendary figures that embody them are perfectly suited to naming stars – but this is not yet a WGSN-wide consensus.

As the IAU wants to represent all people equally and respect all cultures and was founded in 1919 (after the First World War) explicitly to overcome political differences through scientific co-operation, it is important to us to also place names from other cultures in the sky than just the “traditional” Arabic, Greek and Latin ones. Australian and Polynesian names were therefore also placed in the sky in the early years of the group’s work. However, this did not always meet with unreserved approval in the respective culture of origin. Sometimes cultural names are subject to restrictions in their own culture, e.g. that they may only be pronounced by women or only by men. Of course, such names cannot be made official names.

So the questions regarding the naming of stars by the IAU are:

- Where do we get the names from that we make official in the sky?

- What criteria do we use to select from these in order to achieve the widest possible equal distribution and to respect the cultures of origin?

The new suggestion / approach when Susanne M Hoffmann joined the WGSN was (and still is) that we could use the Stellarium repository because it is fed with data by the cultures themselves or respectful researchers. The contributed data is necessarily documented & described (meta-data). If something is in Stellarium, then it must have a licence that allows global use (not always commercial use), i.e. the original culture is respected in any case. The only disadvantage is that the data set is not (and never will be) complete, but we don’t have to name all 8000 stars at once. The problem is similar with lunar craters, for example: you might think, they are all named but still a nameless one can be found if necessary when an important astronomer name is suggested.

Ongoing Discussion

The question that keeps coming up is whether the IAU’s approach itself is overreaching. Of course, the idea of artificially inventing star names and borrowing them from other cultures is a kind of “diversifying with a sledgehammer” and, of course, it is again the overarching community of professional astronomy that assigns the names. You can read this as hegemony or as an attempt to counteract it. There are voices against the use of Aboriginal names (which logically use animals that only exist in Australia, e.g. the emu) for stars in Greek or Babylonian constellations … and there are voices that explicitly demand this.

Other major points of discussion at such highly interdisciplinary meetings are terms (such as constellation, asterism, etc., which are often used differently by amateur astronomers than in the specialised sciences). Of course, we know it is difficult but we also know: If we as IAU succeed in drawing up a common definition that corresponds to all the specialist disciplines, this would simplify the scientific language for the coming decades/centuries – not all amateur astronomers have to go along with this; the main thing is that the specialist world comes to an agreement, as this simplifies interdisciplinary work.

The last word is far from spoken, but it was a fascinating meeting. We had been working together since years but many of us met for the first time in person. We hope that after further remote working, we will get together again in about one to two years and look back on this first meeting as a wonderful kick-off.

Recent Comments